Six years ago, I was studying at Oklahoma University in the USA – for my undergrad year abroad. I’d been excited about living and studying in Oklahoma because classes at the OU School of Meteorology took place in the National Weather Centre in Norman, and also because Oklahoma is in the heart of tornado alley. I’ve always been fascinated by storms (more on that another time), and I was really hoping to have the chance to see some supercells or even tornadoes – and tornado alley did not disappoint!

In the run-up to April 14th, 2012, the whole National Weather Centre was buzzing with anticipation – all anyone could talk about was how perfect the set-up was looking for a tornado outbreak. The storm prediction centre was busy forecasting, researchers were hoping to get some more data, and storm chasers were planning where they might be able to see some tornadoes.

When the 14th came around, I was out chasing storms with some friends from the UK and from OU – and we saw nine tornadoes that day. Below I’ve answered a couple of questions about storm chasing and the science of tornadoes, and you can see some photos from my Spring of storm chasing in tornado alley!

What’s it like to chase tornadoes?

Exhilerating! Tornadoes are scientifically fascinating, eerily beautiful and also terrifying, destructive storms. I’ve seen the damage they can do and it’s so important to listen to warnings and take them seriously, but most of the tornadoes we saw that day were out on the plains away from towns, and they were breathtaking to see. Did you know that storm chasers are also often the first people to see and confirm a tornado, and will phone the relevant services so that nearby towns can be warned? We did just that while we were out chasing!

Exhilerating! Tornadoes are scientifically fascinating, eerily beautiful and also terrifying, destructive storms. I’ve seen the damage they can do and it’s so important to listen to warnings and take them seriously, but most of the tornadoes we saw that day were out on the plains away from towns, and they were breathtaking to see. Did you know that storm chasers are also often the first people to see and confirm a tornado, and will phone the relevant services so that nearby towns can be warned? We did just that while we were out chasing!

At one point, we were driving down a road that suddenly turned to dirt, and we got stuck in a cornfield, when a tornado came down in front of us (but far enough away that we were safe!). We could see the mesocyclone rotating moodily in the darkening sky, and when we turned around, another tornado had appeared behind us. We watched them both form, touch down, move across the landscape and rope out – I have never been more awestruck and terrified at the same time! That day of chasing will remain one of the most memorable days from my year abroad!

How do tornadoes form?

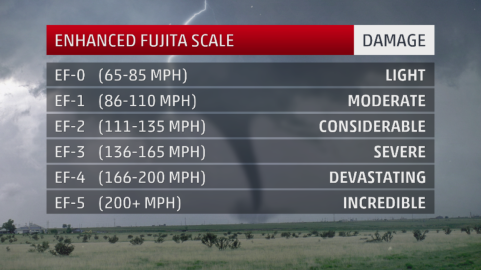

Tornadoes are rotating columns of air reaching from a cumulonimbus cloud or supercell to the ground. They typically have wind speeds ~180km/h and last for 10 minutes or so, but they can get so big that they last more than half an hour, and spin at up to ~500km/h. Tornadoes can also have a diameter spanning anything from 50m to 3km!

Storms that produce tornadoes start off much like any typical thunderstorm – the Sun warms the air near the surface, and as air parcels become warmer than their surroundings, they start to rise. As the air rises, it cools and begins to form clouds. If the atmosphere is unstable, meaning the temperature drops rapidly with height, then large cumulonimbus clouds can form. But to move from a thunderstorm to a supercell capable of producing tornadoes, very specific conditions are required. The wind speed needs to change with height through the atmosphere – this causes a horizontal spin in the atmosphere, which can become tilted to spin in the vertical (the mesocyclone) by the strong updraft of rising air.

Storms that begin to rotate in this way are called supercells, and this rotation is what distinguishes supercells from ordinary thunderstorms. Within the supercells structure, there are also downdrafts of cold air, which act to “concentrate” the rotation, and in some cases (~30% of supercells) this rotation can descend and reach the ground as a tornado.

Does the UK really get more tornadoes than America?

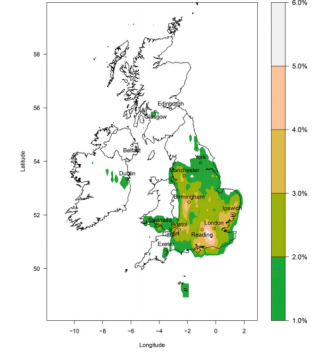

This is a particular favourite fact many people in the UK have enjoyed telling me when I mention I’ve seen tornadoes. But is it really true? Well yes, per unit area, the UK does get more tornadoes than the USA. In fact, per unit area, the UK gets more tornadoes than any other country in the world. But the UK is really very small… so in terms of the actual number of tornadoes, no, the UK does not get more. On average, the UK sees ~30 tornadoes a year, while the USA sees an average of ~1000 each year! While they can indeed be damaging in the UK, they do tend to be weak tornadoes, with 95% of those recorded in the UK being an F0 or F1 typically – and no tornado stronger than an F2 has ever been recorded in the UK.

Researchers at the University of Manchester did some really interesting work recently mapping the places most likely to get tornadoes in the UK – interestingly enough for me, studying at the University of Reading, the most likely place is between London and Reading, with a 6% chance of a tornado occurring in a given year. You can read the article by Mulder and Schultz (2015) in Monthly Weather Review here.

2 thoughts on “Storm Chasing & the Science of Tornadoes”