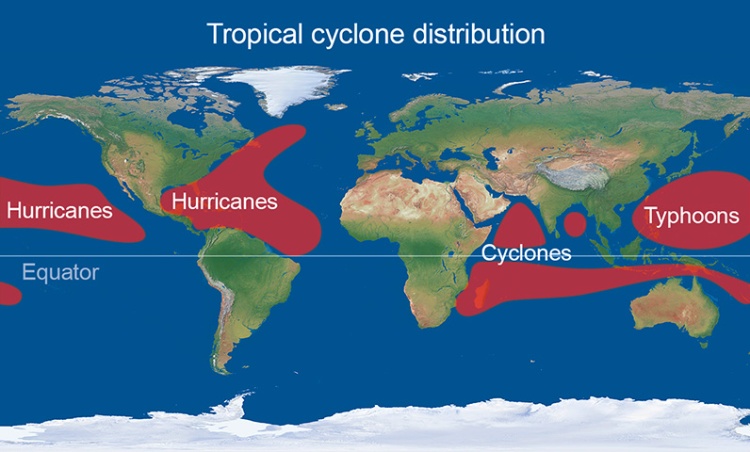

Ever wondered what the difference is between a hurricane, a typhoon and a cyclone? If so, you’re not the only one! And I can answer this one pretty quickly for you: there’s no difference at all! Hurricane, typhoon and cyclone are all different names for the same natural hazard: tropical cyclones. In the Atlantic, they’re usually called hurricanes, in the western Pacific, typhoons, and in Australia and the Indian Ocean, cyclones.

In this blog post, I’ve answered a few questions about tropical cyclones – what they are, how, where and when they happen (& can we get them in the UK?), and what the dangers are. I personally think that they’re one of the most fascinating (and frightening!) types of weather out there and I can talk about them all day – so feel free to ask me questions in the comments below! More on why I’m quite so interested in tropical cyclones another time…

What are tropical cyclones?

Tropical cyclones are essentially storms – large, fascinating, dangerous storms. They form over tropical oceans when conditions are just right, and are called tropical depressions when they first form and are very weak, then become tropical storms, and if they become strong enough, they become tropical cyclones (or hurricanes, or typhoons, or cyclones – depending on where you are!). And when I say they’re “large” storms, I mean huge – often reaching several km in height and 500km wide. The largest (in terms of size, not strength) tropical cyclone ever recorded was Typhoon Tip in the western Pacific, which was ~2000km wide – to put that in perspective, it would have covered almost half of the USA (the lower 48 states, that is). The strongest tropical cyclone in terms of windspeeds was Typhoon Haiyan, also in the western Pacific, with wind speeds exceeding 300km/h!

How do they form?

Tropical cyclones are so-called because they form in the tropics; over warm tropical oceans, thunderstorms often occur. Sometimes, these thunderstorms cluster together and result in plenty of warm air rising rapidly and developing into a low pressure system. If conditions are just right, then the system will start to spin and strengthen into a tropical storm and then a tropical cyclone. For that to happen, the following “ingredients” are needed:

Ocean temperatures of at least 27°C, to a depth of about 50m (this may not sound like a lot, but the global average sea surface temperature is only ~16°C!)

Convergence near the surface (winds blowing from different directions coming together and causing the warm air to rise)

Low wind shear – meaning there must be little change in the wind speed and direction with height, or else the changes in wind with height will prevent the storm from building, or tear apart the storm structure

A distance of at least ~550km from the equator – tropical cyclones can only form further than ~5° latitude from the equator – closer than this, and the coriolis force (caused by the Earth’s rotation) is not strong enough to cause the storm to spin.

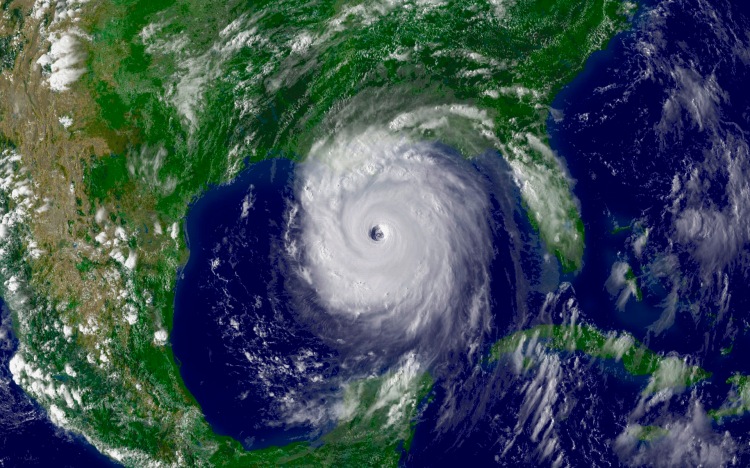

Tropical cyclones also spin in different directions in the two hemispheres, due to the rotation of the Earth. In the northern hemisphere, they spin anti-clockwise, and in the southern hemisphere, they spin clockwise. (Sidenote: it is a myth that water flowing down a drain spins in different directions either side of the equator!)

What are the dangers of tropical cyclones?

Tropical cyclones can have devastating impacts, bringing with them several different types of hazard:

Extremely strong winds and gusts, for a significant period of time (and debris caught up by the wind)

Heavy rain and flooding

Storm surges – the low pressure of the tropical cyclone can cause the ocean to “bulge”, and this combined with strong wind speeds can result in waves that are several metres high, and coastal flooding much further inland than the tide would ever normally reach

Lightning

Tornadoes. When tropical cyclones make landfall, the severe thunderstorms can produce tornadoes, too.

To give you an idea of what hurricane-force winds look (and sound!) like, check out this video from Hurricane Harvey:

The eye of the storm can also be dangerous – at the centre of tropical cyclones, the “eye” is a region, usually a few km across, where the air is sinking, and it’s typically cloud-free and calm. This can be dangerous as people who haven’t experienced a tropical cyclone before may think that the storm has passed and head outside, when in actual fact it’s only half-way, and the strongest winds of all are just on the other side of the eye.

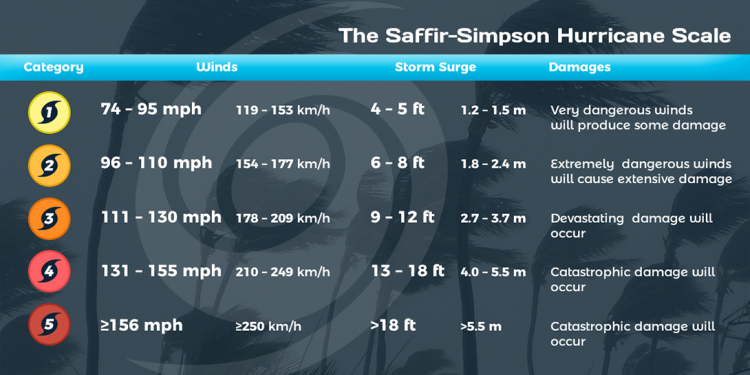

The strength, or intensity, of tropical cyclones can be measured in various ways, but they are categorised according to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale (below). Once tropical cyclones reach land, they begin to weaken, since their energy source is the ocean.

Why do some of them have names?

When tropical storms reach Category 1 strength, they are given names, primarily to make communication between forecasters and the general public easier. In some regions, such as the U.S., an alphabetical list of pre-defined names is used, alternating between male and female names with each storm. Whereas in Asia, the names are often those of flowers, birds, trees etc. Once a tropical cyclone reaches “major” hurricane status (categories 4 & 5), the names are retired and there will never again be a tropical cyclone with that name.

Where and when do tropical cyclones occur?

The map below shows the areas of the world where tropical cyclones occur. In the northern hemisphere, the “hurricane season” is from June to November, and in the southern hemisphere, from November to April. However, they have been known to occur outside of these months on occasion!

Can we get hurricanes in the UK?

In short – no.

There are a couple of well-known instances that spring to mind, of storms affecting the UK being called hurricanes in the media. Take for example Ophelia in 2017, and the infamous Great Storm of 1987. The remnants of hurricanes can indeed sometimes make their way across the Atlantic Ocean to the UK, but by the time they get here, they are much weaker than they would have been further south, and can no longer be called hurricanes. Although that’s not to say that these “ex-hurricanes” can’t have severe impacts in the UK. The official term for these storms once they reach the UK is “extra-tropical cyclones”. And don’t forget, hurricanes require very warm ocean temperatures in order to form – so they definitely can’t form near the UK!

Do you have any other questions about tropical cyclones? Let me know in the comments and I’ll do my best to answer! And stay tuned for more posts on these incredible storms!